Not surprisingly, the backstory behind his invention (search for rubber substitute, unintended results, etc.) shares similar characteristics to James Wright’s version. According to Crayola’s archives, the patent was the result of work Wright began in 1943.Įarl Warrick, an engineer at Dow Corning in Midland, Michigan, also claimed credit for Silly Putty. During one of his failed experiments, Wright had combined boric acid and silicone oil to produce a gooey substance he referred to as “bouncing putty” in the U.S. The most widely accepted story (and the one endorsed by Crayola) attributes the invention of this toy to James Wright, an engineer working for General Electric in New Haven, Connecticut. The quest also resulted in multiple organizations and individuals claiming credit for the invention of the substance that eventually became known as Silly Putty. to take a stab at creating synthetic rubber. Patriotism, the drive for innovation, and profit potential led several notable companies in the U.S. Wartime rationing and a scarcity of the material led the War Production Board of the United States government to fund research by private corporations into synthetic rubber compounds. Silly Putty was invented by accident, the result of a failed experiment undertaken during World War II to develop a synthetic alternative to rubber. Sadly, this feature no longer works with many of the newer inks being used today by the publishing industry.

One of the popular uses of the toy is also my favorite: its ability to copy text and images from comic books and newspapers.

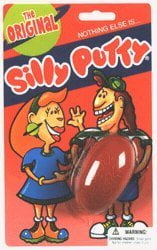

Silly Putty bounces, molds like clay, and stretches like taffy. Currently marketed by Crayola, the appeal of the novelty toy is easy to understand. It is also an apt description of Silly Putty, the ubiquitous “blob of goop” that has, for almost 65 years, provided countless hours of entertainment to millions of adults and children. The phrase “solid liquid” is a textbook example of an oxymoron.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)